Alpha Fusion Insights - November 2023

Superlinear Returns, Demographic Shifts, and the Evolving Landscape of Private Credit

Superlinear Returns, Demographic Shifts, and the Evolving Landscape of Private Credit

The goal of this letter is to spark curiosity and share ideas that help LPs with their long-term thinking. In service of that goal, we discuss three disparate but interconnected ideas this month.

First we introduce the concept of superlinear returns, and how that can shape portfolio thinking and decision making. We then explore how an aging population may cause higher interest rates and higher inflation to last longer than what may be priced in. Finally we explore risks, rewards and incentives in private credit, and implications for LPs.

We end this note with links to 3 articles that caught my attention this month. Fidelity’s inclusion of direct real estate within its Target Date Fund program, the risk to LPs from recallable NAV loans, and OpenAI’s announcement that will revolutionize AI adoption, likely creating new business models and making several business models irrelevant.

Would love to get your feedback on this letter and what we can do to make this more relevant to you. Send me your thoughts at amit.sinha@alphafusion.co.

Superlinear Returns

Concepts that seem obvious after you hear them, but you may not have given much thought to earlier, tend to be most influential in shaping your thinking.

The following, on “Superlinear Returns” by Paul Graham via Shane Parrish and Farnam Street is one such concept. It’s similar to the idea of “power law” but Paul expands upon it:

If your product is only half as good as your competitor's, you don't get half as many customers. You get no customers, and you go out of business.

It's obviously true that the returns for performance are superlinear in business. Some think this is a flaw of capitalism, and that if we changed the rules it would stop being true. But superlinear returns for performance are a feature of the world, not an artifact of rules we've invented. We see the same pattern in fame, power, military victories, knowledge, and even benefit to humanity. In all of these, the rich get richer.

Paul Graham, Superlinear Returns

The concept of superlinear returns has important implications for portfolio construction and active management. Too often managers are comfortable outperforming a benchmark by a few basis points - let's call it linear outperformance. We see this especially with large, established asset managers, who simply need to outperform a benchmark to preserve their AUM. These managers, like any economic agent, are operating to maximize their own utility, but maximizing their own utility leads to undifferentiated outcomes for the allocators/LPs that they serve.

Therefore seeking alpha in a linear world may be a futile exercise for an LP. Instead, ‘linear’ returns (or to be more accurate, returns that lie within the normal bounds of a probability distribution) can be sourced using market ‘betas’, risk premiums, and factors. And then the search of alpha is focused only where the payoffs are superlinear. This combination creates an exceptional investing experience.

Exceptionalism is not easy, it’s uncertain, but it's absolutely worth striving for. Exceptionalism comes with humility and requires patience. It’s about recognizing and embracing the difference between luck and skill, both of which are necessary, neither of which are sufficient.

What’s exceptional for the LP will change over time - our mission is to adapt and help LPs win the superlinear game.

Demographic shifts will cause inflation and interest rates to be higher for longer

In 2022 I had written about how demographics, deglobalization and decarbonization are likely to sustain higher inflation and interest rates for longer. This view is heavily influenced by a BIS Working Paper authored by Charles Goodhart and Manoj Pradhan in August 2017 that focuses on the reversal of global demographic trends that contributed to the last three decades of low rates, inflation and productivity.

After over a decade of low-to-negative real rates, we are now at a point where real rates are mostly positive, inflation is slowing globally but still above central bank targets, growth and unemployment (at least in the US) are at healthy levels. Corporations are generally profitable, but higher interest rates, especially in leveraged credit are beginning to eat into margins and equity returns (more on that in the private credit section of this letter).

There are three main reasons why changing demographics may reduce the certainty by which central banks can influence the economy over the long-term, though they’ll still continue to play a vital role.

First, consumption should increase as the population ages, primarily via greater healthcare spending. Such consumption will be less dependent on wages since retirees are not being supported by wage income. This reduces the correlation between wages and consumption.

Second, governments will likely increase their borrowing to support an aging population, raising interest rates and increasing deficits. Finally, the demographic dividend from the rise of China and other nations that propelled growth, productivity, and kept a lid on inflation is abating.

Figure 1a below describes how consumption rises as individuals grow older, while incomes fall from their peak. When you combine this profile with a shrinking working age population (Figure 1b), it becomes apparent how a larger retiree population can lead to higher consumption (inflationary) and a lower linkage between wages and consumption.

The broader economic effects of demographic change on growth, investment, savings etc. are also interesting to observe. The table below provides the results of an econometric and theoretical study on the consequences of demographic change.

What are the implications of a higher rate regime?

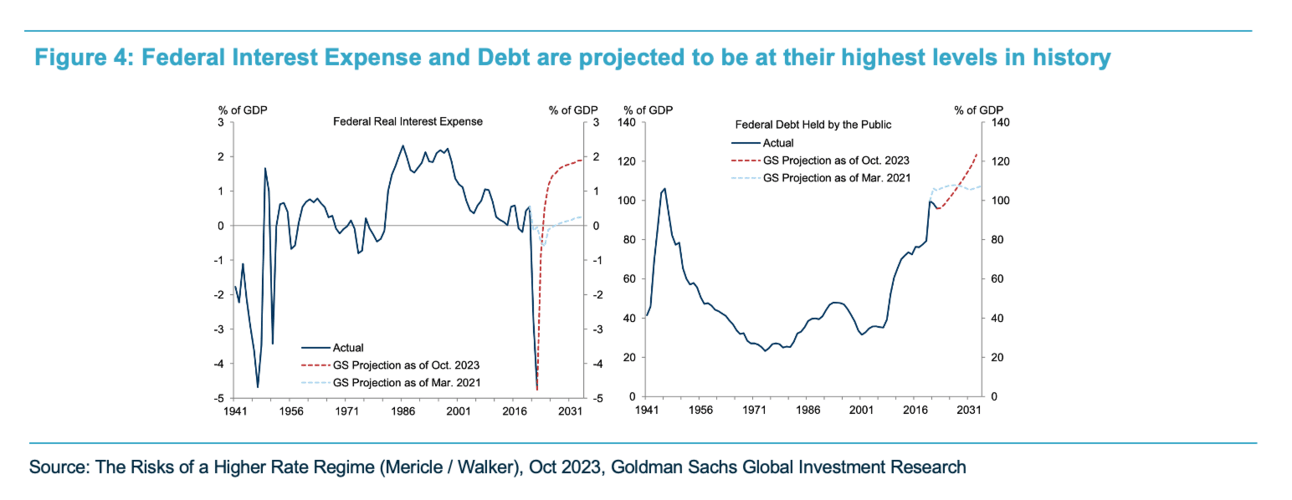

The move to a higher rate regime will impact asset valuations and lead to higher fiscal deficits, though the risk of a recessionary shock remains low. While exogenous shocks are always possible, and generally unpredictable, positive real rates provide central banks with the ammunition to reduce rates to either stimulate the economy, or lower the long-term impact of any exogenous shock.

While many assets have repriced in response to a rise in rates, equities (both public and private), housing, and government debt appear to be stretched, but not close to crisis levels.

Higher Interest rates and federal deficits are likely to feed on each other.

Valuations for both public and private equities are rich relative to the risk-free rate, with private equity earnings yields over the risk free rate turning negative.

The key concern for private market investors will be the survival rate of businesses when faced with a sustained doubling of the cost of capital (higher cost of credit) combined with potentially higher labor costs from a shrinking supply of labor. The rise of unprofitable “Zombie firms” has been linked to availability of credit and lower interest rates.

Implications for Allocators and LPs

A higher rate regime and shifting demographics change the capital allocation game. These shifts transcend the artificial barriers between public and private markets, and link equity and credit closer.

Diversified macro-sensitive risk premiums may be better accessed via public markets using factors, sectors and geographic allocations. In private equity, with no ‘rising tide’ of low inflation and rates to lift all boats, alpha hunting becomes a more concentrated effort, focused on sectors/companies that benefit from these demographic trends, or perhaps focused on opportunities where structuring provides the LP with superior return on capital. Additionally, it may be better for LPs to be a lender at higher rates vs being a borrower provided the total return net of defaults is adequate compensation for the risk and illiquidity being taken.

Which is a good segway into the second topic for this month, which is an examination of the risk, returns and incentive structures across various lenders, and their implications for LPs.

Risk, Reward and Responsibility in Private Credit

The private credit sector is rapidly expanding, with new funds and acquisitions becoming a daily occurrence. LPs find themselves amid a deluge of pitchbooks, each narrative echoing the next, touting selective opportunities and robust underwriting. However, with a glut of over $500B of dry powder, and a revival of competition from banks, GPs may find it harder to be selective, or adhere to the high underwriting standards in the middle of a race to deploy capital.

At the moment private credit does appear to offer a superior return profile for the risks and illiquidity being borne by an LP. However, unlike depositors in banks or policy holders at insurance companies, who are insulated by equity capital, the LP is on the hook for 100% of the losses in a private credit portfolio. This makes it imperative that LPs understand the risks, rewards and incentives across the lending market, and evaluate whether they are at an advantageous position from a risk/return perspective or not.

Such an understanding will be critical for LPs should interest rates continue to remain elevated for longer. An analysis by S&P Global estimates that just 46% of typical private credit borrowers would generate positive cash flows if rates stay higher for longer.

Private Credit is stepping into a world that already exists

Private Credit has grown to over $1.2T in AUM, and is beginning to overlap with other types of lenders.

Source: Carlyle Group

Incentives across the spectrum of lenders – from traditional banks to private credit funds – are diverse. Banks and insurance companies take balance sheet risk, insulating their depositors and policyholders by holding capital that takes losses. As a result, regulations and internal risk management protocols govern the types and levels of risk that they can take. The loan originator’s incentive to lend is tempered by the risk manager’s hold over the balance sheet.

In High Yield and Syndicated Loans, originators are incentivized by flow. While originating banks may have to hold a certain portion of debt on their balance sheet, more often than not the debt is often packaged and sold to other parties. A disparate group of lenders may have less of a say on deal terms, leading to borrower-friendly terms such as ‘covenant-lite’ packages.

In Private Credit, there is a clear separation between the decision maker (the GP) and the risk-taker (the LP). Unlike banks and insurers, 100% of losses flow through to the LP. In the absence of balance sheet and regulatory constraints, a GP is constrained only by an investment process that they deem prudent and sufficient in order to attract and retain investor capital.

The transfer of risk to LPs is a double-edged sword

The lack of constraints is a benefit - an LP may achieve superior returns by accessing good deals that a constrained lender such as a bank or insurer may need to pass on. A GP that negotiates directly with a borrower may secure more favorable terms than a syndicated or high yield deal. Indeed, for similar risks, private credit / direct lending probably offers the highest risk premiums.

However, therein lies a natural tension with LPs bearing the risk while GPs make the lending decisions. With large amounts of capital to deploy amidst increased competition, GPs may be tempted or forced to loosen underwriting standards.

This may not be an immediate issue but should inform an LP’s asset allocation and portfolio construction decisions. As allocations to private credit become a larger portion of an LP’s portfolio, and as the universe of LPs expands from a handful of sophisticated institutions and becomes more democratized (a move that we support), LP portfolios will become more diversified, increasing their exposure to overall market risk while lowering any benefits that concentrated idiosyncratic managers might offer.

Asset Allocation and Risk Overlap in LP portfolios

LPs will need to rethink their approach to asset allocation and portfolio construction. As the figure below illustrates, under the current “asset class” approach, LPs may be doubling or tripling down on the same risk factors, namely exposure to leveraged companies / sectors. Private credit, high yield, and syndicated loans overlap, and higher interest rates effectively transfer cash flows from equity to debt.

It's not a far fetched scenario that an LP could be both a lender to a company through their private credit allocation and a borrower through their private equity allocation.

Source: Alpha Fusion

While some of the larger, sophisticated LPs may have the risk management systems and governance in place to measure these exposures and maximize their returns for risks being taken, a majority of LPs lack the expertise or flexibility.

The need for GPs that serve the LP

The time for an LP focused manager/GP is now. An increasing number of individuals and financial advisors are allocating to private credit, and there is a growing cohort of LPs who are bearing the risk but may not necessarily have the tools to evaluate the risks. Even sophisticated LPs who understand the problem may not have the appropriate governance or organizational structure in place to optimize returns for the risks they take.

This is where GPs can do better. By managing portfolios that solve for the LP. By providing greater transparency - not just data but also analysis. By taking on more of a fiduciary mindset. By being flexible and efficient with capital and risk allocation - having the tools and capabilities to invest and allocate capital across the capital structure and across markets in a manner that maximizes the utility of the risk that the LP is ultimately bearing.

3 things that caught my attention this month:

Recallable NAV Loans - the zero sum game leaving LPs in a bind: Distributions via Recallable NAV loans may go against an LP’s unfunded commitment and therefore create an economic headache. As an LP, you theoretically have the freedom to invest in any asset. It may not make economic sense to be a borrower. Maybe you should be a lender instead? Or identify a cheaper source of leverage?

Fidelity Launches CITs with Alternatives Investment Exposure: As a former member of Voya Multi-Asset Investment Committee, I used to help oversee over $15B in Target Date Fund strategies and had developed the alternative strategies used within these funds. I see Fidelity’s announcement as a net positive for the democratization of alternatives, though I believe a lot more needs to be done on product design and investment strategy to ensure that true ‘alternative alpha’ along with lower volatility makes its way into retirement portfolios. Solutions are available that can offer reasonable liquidity, lower observed volatility, and diversified alternatives exposure at a reasonable cost. Reach out to me if you would like to discuss further.

OpenAI’s DevDay: A lot has been written about OpenAI’s Dev Day. OpenAI’s first developer day saw the unveiling of features that will transform how we live and work in the coming years. Regardless of your philosophical or emotional stance on AI, this will have investment implications. Conor Grennan of NYU provides a good 6 minute video summary:

What I am currently reading:

Non fiction - Chip War

The Financial Times Business Book of the Year, this epic account of the decades-long battle to control one of the world’s most critical resources—microchip technology—with the United States and China increasingly in fierce competition is “pulse quickening…a nonfiction thriller” (The New York Times).

Fiction - The Essential Tagore

The Essential Tagore showcases the genius of India’s Rabindranath Tagore, the first Asian Nobel Laureate and possibly the most prolific and diverse serious writer the world has ever known.

Marking the 150th anniversary of Tagore’s birth, this ambitious collection―the largest single volume of his work available in English―attempts to represent his extraordinary achievements in ten genres: poetry, songs, autobiographical works, letters, travel writings, prose, novels, short stories, humorous pieces, and plays. In addition to the newest translations in the modern idiom, it includes a sampling of works originally composed in English, his translations of his own works, three poems omitted from the published version of the English Gitanjali, and examples of his artwork.